MRE Depot

Military Surplus Hardtack Army Bread, Ready to Eat (#10 Can)

Military Surplus Hardtack Army Bread, Ready to Eat (#10 Can)

Can

Shop location

942 Calle Amanecer

Suite B

San Clemente CA 92673

United States

Military Surplus Ready To Eat Hardtack Army Bread

Built to last. Ready when you are. This Military Surplus Hardtack Army Bread is the ultimate in time-tested survival food—baked to be tough, packed to endure, and sealed for a 30-year shelf life. This is the same style of hard bread that sustained soldiers and sailors through history, now modernized and sealed in a durable #10 can for long-term emergency preparedness. Whether you’re stocking up for disasters, prepping your bug-out bag, or just paying homage to rugged history, this hardtack delivers.

Let’s take it back to the basics—way back, like 1800s frontier back. Before fast food, before the corner store, before refrigerators, before preservatives, before canning, before the first meal-ready-to-eat (MRE), before Pop-Tarts and protein bars, there was Hardtack - the flat, hard cracker that stood the test of time. This humble disc of flour and salt WAS the survival ration. As an ancient survival ration, hardtack (aka Ship’s Biscuit or Hard Bread), powered sailors, soldiers, and settlers across oceans, battlefields, and untamed frontiers. A simple, rock-hard biscuit made to survive harsh weather, long journeys, and the kind of storage conditions that would make a loaf of modern bread cry. Made from simple ingredients: flour, water, and salt, this sturdy cracker would provide sustenance even under the harshest conditions.

Used by soldiers, pioneers, and adventurers alike, hardtack was the ORIGINAL emergency food: sturdy, shelf-stable, and nearly indestructible. And now? It’s still got a place in today’s world—whether you're building an emergency food kit, heading off-grid, or just fascinated by historical cooking.

While not the most flavorful food item at the time, hardtack served its purpose by providing much-needed calories and energy for soldiers enduring long marches and battles. It was part of the Holy Trinity of a soldier’s diet, alongside salt pork and beans/peas—and in many cases, all three would be combined for an unforgettable meal.

Flash Facts:

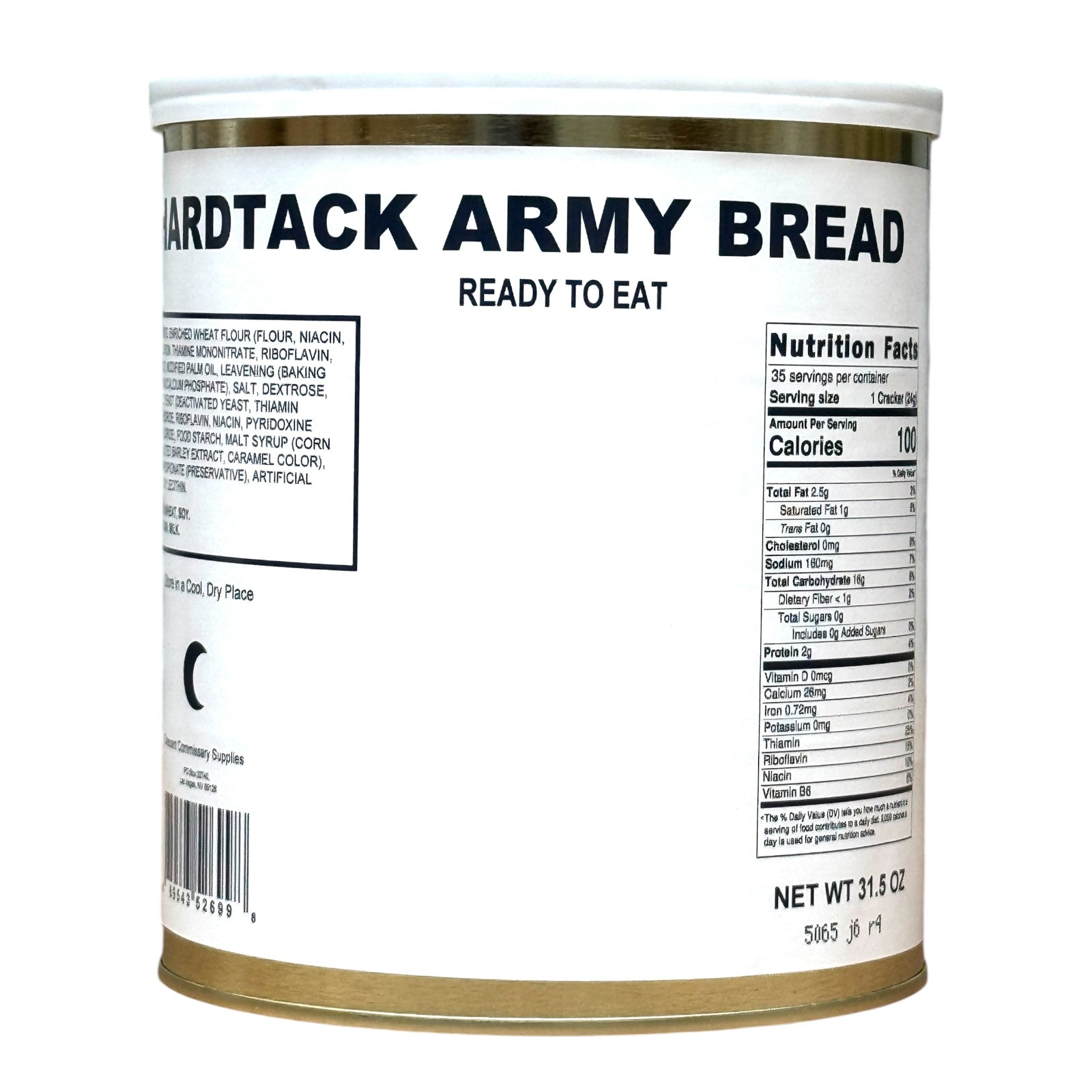

- #10 Cans (aka Gallon size can)

- 34 to 36 Hardtacks per can (31.5 oz per can)

- US Government/Military Surplus

- 30+ years shelf life

- September 2025 production date

Hardtack Army Bread – Authentic Ship’s Biscuit in #10 Can

Baked to outlast storms, soldiers, and centuries.

This Hardtack Army Bread is a faithful, rugged tribute to the original Ship’s Biscuit—a food that kept explorers, navies, frontiersmen, and Civil War soldiers going when nothing else would. Sailors on 18th-century ships didn’t get three meals a day with fresh ingredients—they got a pound of this bread every day. That meant six or more thick, hockey puck–shaped biscuits, baked low and slow until they were rock-hard, shelf-stable, and virtually immortal. This was their daily ration, and they learned to love it—or at least accept it. Some sailors even preferred hardtack after months at sea, believing soft bread could upset their digestion.

And it wasn’t just sailors. Revolutionary War soldiers, westward-bound settlers, and Civil War infantry all relied on this kind of bread. Diaries from the time don’t even call it “hardtack”—they just call it bread. Because for them, it was.

Hardtack is often referred to as the original MRE (meal ready to eat) because, much like today's ration packs, it was convenient, portable, and could be consumed without immediate preparation. But unlike modern MREs, this one was designed to last—a lot longer.

Built Like a Brick. On Purpose.

Ship’s biscuits were made from the simplest recipe imaginable—flour, water, and maybe a pinch of salt. But don’t let the ingredients fool you. The technique was everything: you needed a stiff dough, no cracks or folds, shaped just right, then dried out completely. Baked low and slow—sometimes for days—to keep every ounce of moisture out. Because moisture meant mold. Moisture meant bugs. Dry meant survival. And they were made to last.

From the Texas Revolution to World War I, hardtack was a staple in the rations of soldiers on both sides of major conflicts. For those traveling or at war, it was the ideal food: cheap to make, easy to carry, and incredibly resilient. But its durability came at a cost—flavor.

Soldiers and explorers had their own methods for making it more palatable:

- Soaked in water, coffee, or broth to soften it.

- Mushed and fried with grease or sugar to make skillygalee.

- Fire-blackened and ground into a powder to make imitation coffee.

While it wasn’t a five-star meal, hardtack kept people alive—and that’s why it was so cherished.

Yes, You Could Make It Yourself… But Why?

Sure, the ingredients are simple. But this isn’t your average loaf of bread. If you really want to mix the dough, roll it flat, poke it with holes, and babysit it in a low oven for hours (or even overnight) just to end up with a food that could double as a building material… well, we respect that. But for most folks, opening a #10 can is a lot easier. And probably safer for your teeth too.

What’s Inside?

This military surplus version adds just enough modern practicality to make it legal and safe for long shelf life—but the spirit is all 18th-century. It’s still dense, dry, unyielding, and somehow satisfying. Just like the old days.

Taste History. Eat Like a Sailor. Survive Like a Soldier.

Whether you're stocking a prepper pantry, reenacting life aboard a man-of-war, or just curious what food was like before preservatives and delivery apps, Hardtack Army Bread is as real as it gets. Grab a can. Crack it open. Chew carefully.

Because this isn’t just food.

It’s survival in a biscuit.

Why Hardtack Still Matters Today

You don’t need to be in the middle of a military campaign or a 19th-century exploration to appreciate hardtack. It’s still used today in emergency preparedness and survival food storage, as its longevity and ease of use remain unmatched. Whether you’re stocking up on emergency rations, participating in a historical reenactment, or simply curious about the food that sustained generations before us, hardtack brings a unique connection to the past.

A Journey Through Time: The History of Hardtack

Hardtack has been known by many names across history, from the Egyptian mariners calling it "dhourra" to Roman legions referring to it as "buccellum." The British coined the name “hardtack,” and it was soon adopted by sailors, soldiers, and pioneers across the world. In fact, this simple but reliable food source has been around for over 6,000 years, with the oldest pieces discovered dating back to ancient times.

The Story Behind Hardtack on the Columbus' journey

On August 3, 1492, Columbus set sail from Palos, Spain, aboard the Niña, Pinta, and Santa María. Despite facing rough seas, overcrowded ships, and imminent mutiny, Columbus and his crew endured a grueling 35-day journey across the Atlantic. Part of their survival was due to hardtack, a simple yet effective food.

Hardtack biscuits were made by baking flour and water into a solid, rock-hard dough that could last for months without spoiling. Hardtack biscuits was vital in preventing starvation. These biscuits were often softened in water or dipped in a communal soup, making them essential for keeping the sailors fueled for their long voyage.

The Story Behind Hardtack on the Mayflower

In 1620, the Pilgrims boarded the Mayflower for their harrowing journey to America. With no ability to cook, the 102 passengers survived primarily on preserved foods, including salted meats, dried fish, and—most importantly—hardtack. These simple, long-lasting biscuits were a vital part of their diet during the 66-day voyage. Although they were difficult to eat due to their dry, hard texture, they were one of the few foods that could endure the rough seas and harsh conditions of the journey.

The Pilgrims and their fellow passengers spent most of the voyage squeezed into cramped, cold, and damp quarters with little access to fresh food or water. With no refrigeration, regular bread would have spoiled quickly, so they relied on hardtack to sustain them. Hardtack biscuits served a vital purpose: providing much-needed calories and nutrients during a journey that was anything but easy.

Hardtack in the Civil War: The Soldier's Brick Bread

During the Civil War, Union soldiers carried a special kind of food called hardtack — a dry, tough cracker made from flour, water, and salt. It was so hard they nicknamed it “sheet iron” or “tooth duller.” But it lasted forever and gave soldiers the energy they needed on long marches.

To make it edible, soldiers soaked it in coffee. Some crushed it with their rifle butts and tossed it into stews with salt pork and scraps. Others fried it in bacon grease to make something called skillygalee. If they were lucky, they could buy sweetened milk from a traveling merchant, called a sutler, and mix it with the cracker to make a simple treat — though most couldn't afford it.

Meanwhile, Confederate soldiers often didn’t have wheat for hardtack. Instead, they made Johnny cakes or corn dodgers from cornmeal, salt, and water — just as hard, but from Southern crops. When they could, they fried them in fat and called the dish cush.

Even though soldiers complained about hardtack, it was always there — stuffed in their packs, floating in their coffee, or sizzling in a skillet. It was a tough food for tough times, and for many, it tasted like survival.

U.S. Military Hardtack Crackers – The Field-Tested Bread of War

Hardtack-style crackers have carried American soldiers through every major military conflict of the 20th century — from the foxholes of France in WWI to the humid rice paddies of Vietnam. These rock-solid, shelf-stable biscuits weren’t just food — they were survival. Packed in rucksacks, ration cans, and ammo pouches, they fueled the U.S. military on land, at sea, and in the air.

This is more than just a cracker — it’s a legacy of endurance, invention, and shared hardship. Our military-style hard crackers are inspired by the original recipes used in U.S. Army C-rations and MCI (Meal, Combat, Individual) units — rough, rugged, and ready for anything.

Starting in the early 1900s, military rations began evolving — but one thing remained consistent: you needed a dry, compact, non-perishable carb source. Enter: the military cracker.

From Reserve Rations in World War I to C-rations in World War II, and later to the MCI rations used in Korea and Vietnam, hard crackers — sometimes called “bread,” “biscuits,” or “crackers, unit” — were issued alongside spreads, canned meats, powdered drinks, and sweets. They were the only form of bread many troops had access to for weeks at a time.

How Soldiers Actually Used Them:

- As-Is: Troops often joked that hardtack could double as a building material — and they weren’t wrong. These things were hard. Soldiers sometimes broke them open on rocks, rifles, or tank treads.

- With Canned Cheese or Peanut Butter: C-ration “B-units” included spreads like processed cheese or peanut butter. These were slathered onto the crackers to soften them and add flavor. For some, this was the best part of the meal.

- Crushed into Soups or Stews: Many soldiers broke crackers into their hot meat rations or heated cans of beef stew or beans. It turned cracker powder into a thickening agent and added bulk to meals.

- Toasted or Cooked in the Field: If a fire or heat tab was available, troops sometimes toasted them or cooked them into primitive “field casseroles.” A little water, heat, and ingenuity turned these bricks into something edible — or at least chewable.

- As Card Game Currency: When not eating them, soldiers gambled with them. Crackers were uniform in shape and size and practically indestructible — perfect poker chips during downtime between missions.

Over the years, these crackers were issued to:

- WWI Doughboys in France (Reserve Rations)

- WWII GIs storming beaches and holding lines (C-rations)

- Korean War troops freezing in the mountains (MCI units)

- Vietnam-era soldiers and Marines, who learned to drown their cracker crumbs in coffee, spread them with John Wayne Cheese, or crush them into “foxhole fondue”

They were the one part of the ration everyone could count on — for better or worse. They didn’t spoil, didn’t leak, didn’t rot. They sat quietly in their tin cans, waiting to be cracked open in the field, where they’d remind you that someone somewhere was thinking about how to keep you alive another day.

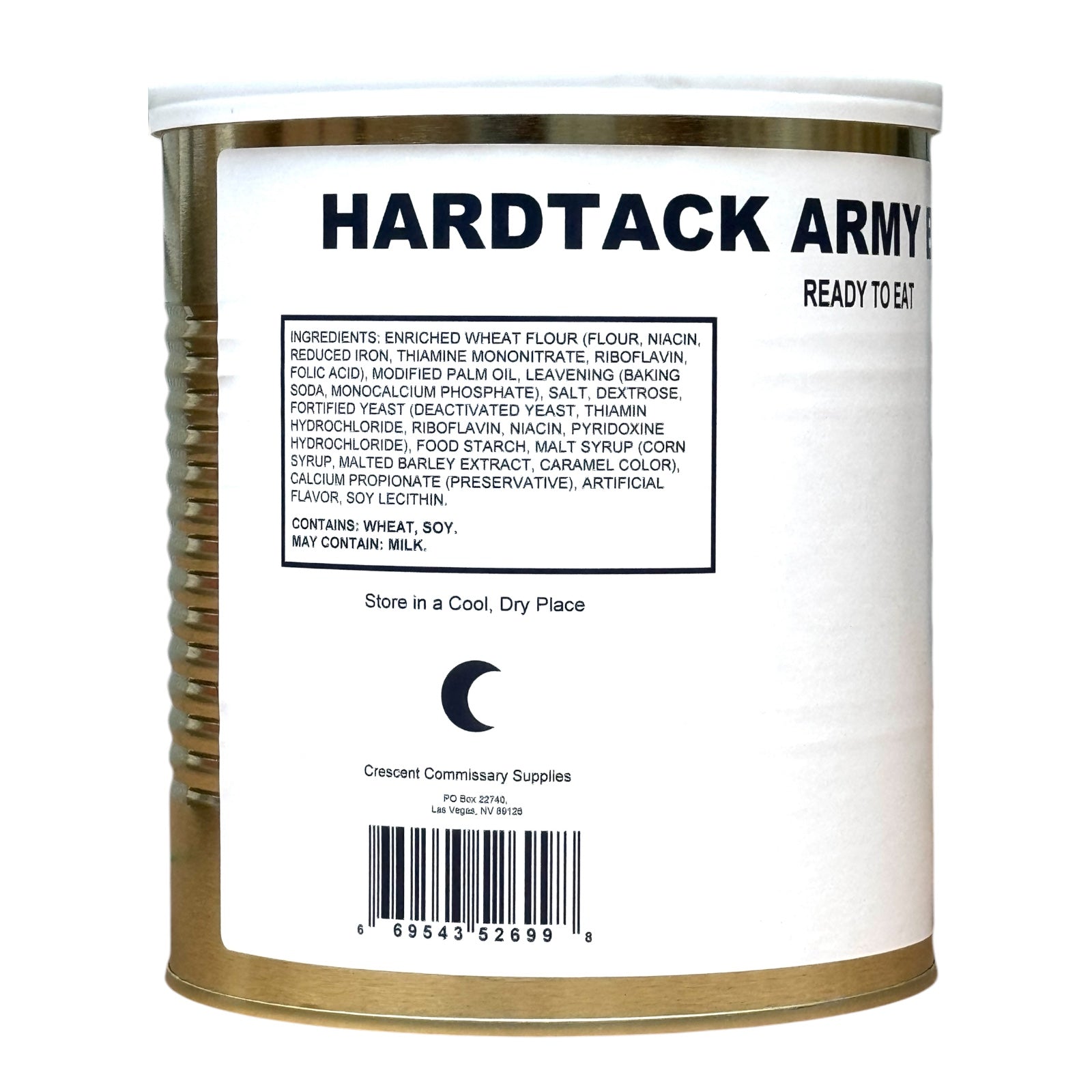

Ingredients: Enriched Wheat Flour, Modified Palm Oil, Leavening, Salt, Dextrose, Fortified Yeast, Food Starch - Modified, Malt Syrup, Calcium Propionate, Artificial Flavor, Soy Lecithin.

Contains: Wheat, Soy.

Manufactured, Procured, and Canned in the USA